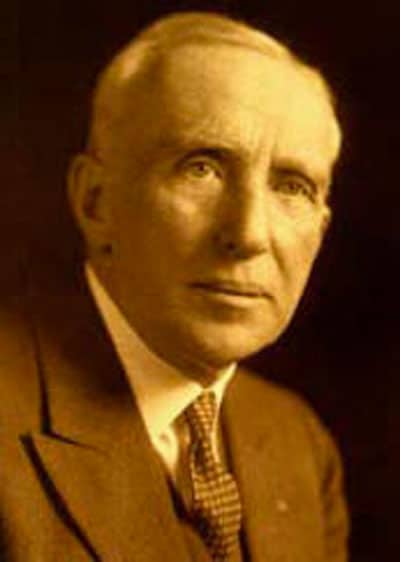

In 1914, Max Aaron Goldstein, MD, a renowned St. Louis ear, nose and throat physician, set out to do what most people believed impossible: teach deaf children to talk. During his postgraduate medical training in Europe, he had met a Viennese professor teaching deaf children to talk using “remnants” of hearing. This experience became the genesis for his dream to convince the world that congenitally deaf children could learn to listen and speak intelligibly.

Realizing the Dream

Encouraged by his friend Helen Keller, Dr. Goldstein began an aggressive campaign to pursue his dream when he opened Central Institute for the Deaf – the first fully dedicated listening and spoken language school for children with hearing loss in the United States. His idea was to create a place where doctors and teachers would work together to improve ways to help deaf children. At first, he devoted two rooms of his St. Louis medical office to educating deaf children and training teachers of the deaf. His services included auditory-oral deaf education for children (now called listening and spoken language), counseling, a hearing clinic, lipreading instruction and speech correction for children and adults. To his ongoing medical research, he added studies using early devices such as hearing tubes and ear trumpets in the classroom.

Leaders from the academic, business and medical communities supported Dr. Goldstein’s dream. The first CID school was completed in 1916. By the late 1920s, CID’s reputation for success had led to burgeoning enrollment and waiting lists. In 1929, a second building was added to house laboratories, classrooms and dorms. Teachers measured children’s progress in response to new listening devices and educational strategies. Scientists came from throughout the world to study the anatomy of animals’ ears, the science of hearing devices, techniques for diagnosing deafness, psychology and deafness, the sound of deaf children’s voices and related topics.

From the beginning, Dr. Goldstein built CID’s reputation by demonstrating the school children’s success at professional conferences for doctors and teachers across the country. He was also a shrewd PR man, with an open-door policy for the press — for example, any time CID trialed a new hearing device in the classroom. Over time, hundreds of articles were written locally and nationally about CID.

Shaping Education & Science

In 1931, CID’s Teacher Training College affiliated with nearby Washington University, becoming the country’s first deaf education teacher training program to affiliate with a university. By 1947, when S. Richard Silverman, PhD, became director, CID offered graduate programs in deaf education, communication sciences and a new profession, audiology. CID opened the nation’s first hearing aid clinic and CID scientists were instrumental in developing the science and academic field.

CID was also a pioneer in the early intervention and education of deaf children. For the first two decades, it was the only school of its kind teaching 3-year-olds. In 1933, using tools from the budding discipline of psychology, CID’s principal, Dr. Helen Schick, proved to the world that deaf children were equally as intelligent as children who could hear. Later that decade, CID teachers developed the Language Outline, an early model for teaching language, as opposed to just vocabulary, to children who were deaf and hard of hearing. In 1958, CID’s parent-infant program became the first program of its kind and a model for programs throughout the world.

Succeeding CID clinical and educational researchers followed Schick’s lead. In 1981, CID’s landmark EPIC Study proved that highly individualized, ability-grouped auditory-oral deaf education significantly increased the achievement of deaf school children. Since then, CID educational researchers have produced a variety of niche tools, including the TAGS, GAEL, SPINE, CID Phonetic Inventory, ESP, CID SPICE and SPICE for Life auditory learning curricula, Small Talk and Early Listening at Home. CID curricula and resources are used across the country and worldwide in schools, clinics, university textbooks and the homes of families of babies with hearing loss.

In 2000, after a successful capital campaign, CID completed a new campus. The state-of-art facilities feature a specially designed “quiet school,” built for children learning speech and spoken language, audiological facilities in the Spencer T. Olin Clinic, and research laboratories in the Harold W. Siebens Hearing Research Center.

Revitalizing the Mission

In 2003, CID entered into a historic agreement to formalize ties with Washington University, its School of Medicine and Department of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. Under the terms of the agreement, Washington University School of Medicine assumed ownership and governance of CID’s adult-focused programs, creating CID at Washington University School of Medicine. Central Institute for the Deaf remained separate and financially independent from the University, which continues to operate research and graduate degree programs on the CID campus on Clayton Avenue in St. Louis, Missouri.

At that time, CID created a new main entrance at 825 S. Taylor Avenue, where we continue to offer outstanding early intervention services, preschool- and school-age educational programs, expert onsite pediatric audiology and speech-language pathology and classroom-trialed educational curricula, continuing education courses and other professional development resources. https://professionals.cid.edu.